In its 3Q15 earning call, CVS explained that its margins declined due to higher proportion of lower margin Medicare and Medicaid business. Here I want to focus on Medicare, and specifically Medicare Part D (the drug portion), which obviously have big impacts for the PBMs (CVS, ESRX), pharmacies (WBA, RAD), and the rest of pharmaceutical supply chain from distributors to drug manufacturers.

Pharmacies like WBC have been talking about drug reimbursement pressure for a while. Much of that stems of their weaker bargaining position relative to PBM and payers. But what has not been discussed enough is that Medicare Part D revenue per member has deteriorated several years in a row.

Reimbursement Pressure Starts at Health Plans and Propagate Through Supply Chain

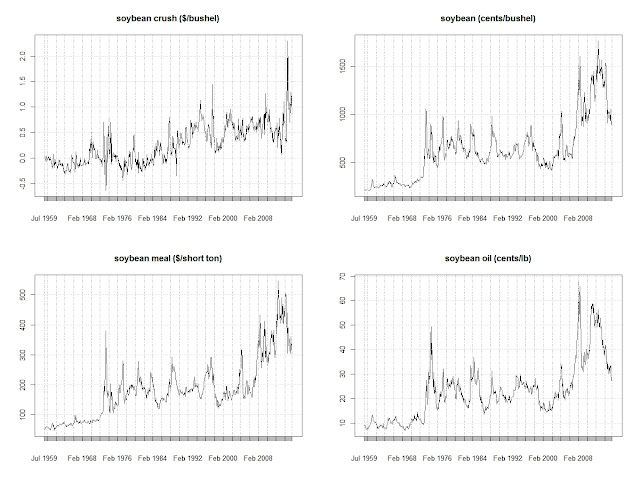

There are lots of online articles on drug costs to the enrollee, but figuring out what the government pays health insurance companies is not straight forward. Fortunately, chapter 6 of this Medpac report has a detailed explanation of how Part D reimbursement works, and even an example of how plans bid. From the same report (shown below) is Medpac’s measure of government outlay in Part D plans.

From this chart it’s clear that “expected reinsurance” has been steadily increasing, while “base premium” and “direct subsidy” have been steadily decreasing. A quick note about how this works. “Direct subsidy” is what government pay to health plans directly. “Base premium” is what enrollees pay. “Expected reinsurance” is what government reimburse the plans after drug costs exceed some catastrophic threshold.

From this chart it’s clear that “expected reinsurance” has been steadily increasing, while “base premium” and “direct subsidy” have been steadily decreasing. A quick note about how this works. “Direct subsidy” is what government pay to health plans directly. “Base premium” is what enrollees pay. “Expected reinsurance” is what government reimburse the plans after drug costs exceed some catastrophic threshold.

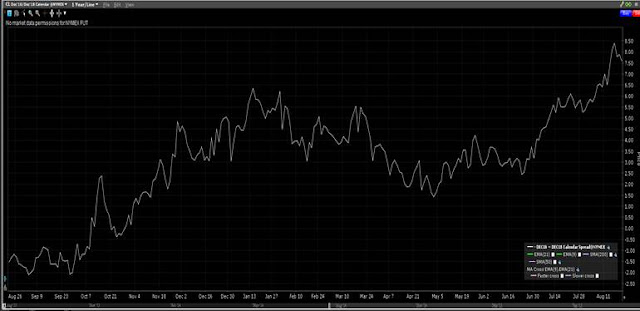

Since reinsurance is used to cover catastrophic drug costs, what the plans really get is direct subsidy and base premium, or what CMS calls the “National Average Monthly Bid Amount”. This is a good proxy of a health plan’s revenue, from which it needs to cover drug costs (below the catastrophic threshold) and administration costs, with the remainder going to plan profit *. The table below show that the average bid amount has been declining steadily, which led to reimbursement pressures throughout the entire drug value chain. For 2016, the industry will see another steep drop of 7.6%.

Why is this happening? First, what is not an adequate is the argument that health plans are not actually seeing reimbursement pressure, because the overall bid amount including reinsurance has actually been increasing. From the plan’s perspective, reinsurance just compensates for extraordinary costs and does not add to the bottom line. As for the base elements, even the MedPac report cited above - which alleges that sponsors use clever bidding strategies to maximize profits - the example given (page 163, table 6-11) clearly shows that gaming the bid system would lead to higher, not lower bid amounts (Case 3 in the example is what the plans have been doing. Based on actual claim experience the direct subsidy and beneficiary share should have totaled $46.50, but the plan bid totaled $60.00 those items).

So the way to reconcile a) ever higher reinsurance payments with b) ever lower bid amounts is that government and private sectors are both sharing the pain of higher drug costs. The government has been taking on more catastrophic risks, while private sector focused on efficient day to day administration. In this way both utilize their comparative advantage.

So the fact that bids amount have been lower every year is not about plans ripping off the government, but due to genuine industry competition. There are various explanations:

The above drivers are not about to go away soon, so this trend of lower bids and worse economics for entire drug value chain could continue for a while. In the longer term though, large players like CVS and UnitedHealth might actually benefit as lower margins drive out smaller competitors. In terms of ability to withstanding constant Part D reimbursement pressure, I would rank the various players from best to worst as follows.

I am holding on to my UNH and AET shares despite the political rhetorics sure to come in 2016. I particularly like the idea of a combined AET/HUM dominating the growing Medicare business. CVS is a tough call as it a well-run company but its pharmacy business will likely bear reimbursement pressure for years to come.

Reasons for the Decline

Why is this happening? First, what is not an adequate is the argument that health plans are not actually seeing reimbursement pressure, because the overall bid amount including reinsurance has actually been increasing. From the plan’s perspective, reinsurance just compensates for extraordinary costs and does not add to the bottom line. As for the base elements, even the MedPac report cited above - which alleges that sponsors use clever bidding strategies to maximize profits - the example given (page 163, table 6-11) clearly shows that gaming the bid system would lead to higher, not lower bid amounts (Case 3 in the example is what the plans have been doing. Based on actual claim experience the direct subsidy and beneficiary share should have totaled $46.50, but the plan bid totaled $60.00 those items).

So the way to reconcile a) ever higher reinsurance payments with b) ever lower bid amounts is that government and private sectors are both sharing the pain of higher drug costs. The government has been taking on more catastrophic risks, while private sector focused on efficient day to day administration. In this way both utilize their comparative advantage.

So the fact that bids amount have been lower every year is not about plans ripping off the government, but due to genuine industry competition. There are various explanations:

- The “National Average Monthly Bid Amount” is weighted by enrollees. So as low cost plans win over more enrollees the weighted average would be dragged down.

- The larger plans have been aggressive as scale allows them to lower operating expenses and push through formulary changes.

- Generic conversion have lowered regular drug cost, while government took on the tail risk of the Sovaldi/Harvonis of the world.

- Medicare Advantage plans with drug benefits (MA-PD plans) can bid lower as the Part D is small portion of overall revenue (Part D bid amount will be $64.66/month in 2016E, while Part C benchmarks are easily $750-800/month)

Investment Implications

- Managed care companies. (UNH, AET, HUM) Medicare Part D in general is a smaller part of their business. If the Aetna/Humana merger goes through, the combined entity will be a major player in MA-PD plans and can continue to push bids lower to take market share.

- Standalone PDP / PBMs (CVS and ESRX). Both CVS and ESRX are large players in the standalone PDP space. They are at a disadvantage relative to managed care companies but have been able to exert strong bargaining power over the rest of the supply chain.

- Pharmacies (WBA, RAD) and drug distributors (MCK, ABC, CAH). These have weak bargaining power. The pharmacies in particular have been beaten up by PBMs. Their only hope is more consolidation as in the Walgreens Rite Aid deal. The major pharmacies and drug distributors have also teamed up to get more market power.

I am holding on to my UNH and AET shares despite the political rhetorics sure to come in 2016. I particularly like the idea of a combined AET/HUM dominating the growing Medicare business. CVS is a tough call as it a well-run company but its pharmacy business will likely bear reimbursement pressure for years to come.

* Notes: Some analyst reports calculate plan revenue as average bid amount + enrollee premium. That is incorrect, as the enrollee’s base premium is calculated as a percentage of the National Average Monthly Bid Amount, which implies the latter is inclusive of enrollee premiums)